Il 7 novembre 2025 è uscito il disco Lux di Rosalía ha fatto uscire il suo disco Lux, il quarto della sua discografia. Dopo il successo indiscutibile di El Mal Querer (2018), che le è valso quattro Latin Grammy, tra cui quello di Album of the Year e il Grammy Award for Best Latin Rock, Urban or Alternative Album, Rosalía ha travolto lo spazio musicale con Motomami (2022): un “concept album di natura minimalista” – come lo descrive la cantante catalana – che l’ha fatta emergere come musicista e artista di spicco. È la prima donna a vincere il Grammy Award for Album of the Year per ben due volte.

IIl successo diventa ancora più impressionante se si considera la varietà dei progetti. L’inquieta forza creativa emerge dall’intervista rilasciata a Zane Lowe per Apple Music[1]. Il giornalista neozelandese interroga Rosalía sul sentimento di “mutilazione continua” che la coglie quando rigetta le sue creazioni. Rosalía non solo è conscia del proprio comportamento, ma anzi spera di potrarlo, in modo che “l’identità possa morire e nascere, che ogni giorno sia un giorno per decidere chi si è.”

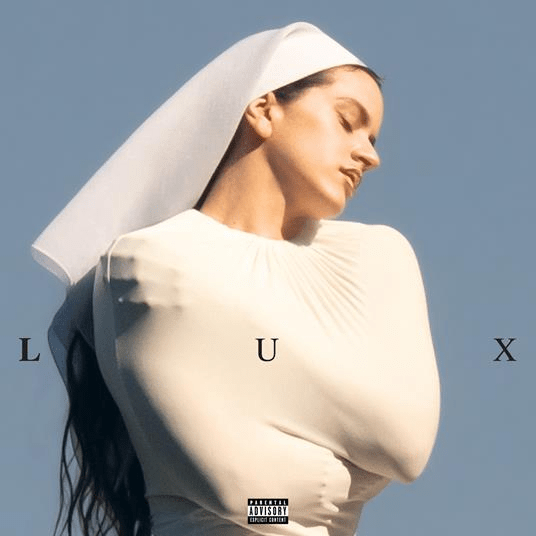

Le scelte del progetto creativo di Lux sono, dunque, intenzionali a partire dalla copertina, che è molto diversa dalla precedente (Motomani). Lì l’immagine dell’artista nuda coperta solo dalle mani non lasciava intravedere il volto, nascosto da un casco integrale che lascia liberi i lunghi capelli mossi dal vento. In Lux accade il contrario: l’artista appare coperta da un tessuto bianco e i capelli sono ordinatamente nascosti da un velo.

L’immagine ricorda Il Cristo velato di Giuseppe Sanmartino. In una luce raggiante, che possa provenire sia dall’interno che dall’esterno, Rosalía rivela il volto che finora ci celava.

La prima impressione che suscita album pop è importante. Questo Rosalía lo sa bene. Usare la parola pop in questo contesto non avviene senza un certo disagio, ma se la cantante ci ha voluto insegnare qualcosa con la sua arte, è che la sua classificazione in questa o in quell’altra categoria risulta fuorviante per la comprensione della sua arte. Il messaggio è semplice: Lux non è Motomami.

È massimalismo contro minimalismo, un’orchestra intera che ruggisce contro i tagli e loops che caratterizzano l’ultimo disco. Molti si sono affrettati ad assumere che “Berghain”, il titolo di una dei brani di Lux, si riferisse alla nota discoteca berlinese dallo stesso nome, luogo che Rosalía ammette di non aver mai avuto il coraggio di frequentare. L’artista ci dice, invece, che il titolo è la traduzione letterale del tedesco: un boschetto di montagna. Rosalía ci spinge, dunque, a pensare ai “labirinti di boschetti che esistono nelle nostre menti”. Mi fa pensare alla selva oscura di Dante. E da qui un bisogno di luce che è un percorso teologico.

Nella luce, attraverso la selva, verso l’altro. Rosalía descrive la sua vita tra incisioni di album come un tempo di riflessione, autocomprensione, isolamento e studio. Tuttavia, non è unicamente un tempo introspettivo né eremitico. Lei si affida ai consigli della sua cerchia più ristretta: i suoi colleghi producers, i suoi amici, la sua famiglia e in particolare sua sorella Pili. “Perché devi sempre distruggere la canzone?” è stata la questione posta da Pili quando ascoltò le canzoni di Motomami per la prima volta. Rosalía ammette che, in un primo momento, si è messa sulla difensiva mentre cercava di giustificare questa distruzione. In effetti, alcune canzoni su Motomami assomigliano più a un bricolage di diversi flussi di coscienza, piuttosto che la sintesi di un unico pensiero. Rosalía riconosce che, in quanto musicista, è chiamata a far sentire. Tuttavia, in Motomami, ha scritto senza completare il pensiero, frenandolo bruscamente prima di giungere alla fine. Lux mostra un desiderio di andare verso la pienezza. Si chiede: “Fino a dove riesco ad arrivare con questo pensiero?” senza dover compromettere la sua libertà artistica negli arrangiamenti musicali.

Rosalía ferma l’inseguimento ad alta velocità per prestare attenzione a ciò che il suo cuore desidera. Rivela che la creazione di un album le serve per approfondire un tema che in questo caso è la teologia. El Mal Querer era stato originariamente concepito come la sua tesi di laurea al conservatorio. Se Rosalìa non avesse intrapreso una carriera musicale – ammette lei stessa – sarebbe nelle aule di teologia all’università. Il suo interesse non si limita al cristianesimo, ma include biografie e racconti di più tradizioni religiose: i xian del taoismo, i tzaddikim nell’ebraismo, i rishis nell’induisimo, gli awliya Allah (amici di Dio) nell’islam.

In questo senso, Rosalía sembra una teologa. Nell’anno dedicato alla stesura dei testi di Lux, ha trascorso il suo tempo tra lettura e scrittura, creando anche un mapa mundi e consultando diverse agiografie, “tutto nel tentativo di raggiungere l’altro.” Spiega a Lowe: “Raccogliendo i vissuti dell’altro, […] creando canzoni ispirati in essi, sto celebrando e dando amore all’altro, all’alterità- cercando di comprendere meglio l’alterità.” Lei riconosce il peso delle sue parole mentre riflette sulle polarità e divisioni presenti nel mondo d’oggi e protesta: “No! Voglio il contrario! Ho bisogno del contrario!”

Rosalía si attrezza nel suo viaggio verso l’altro studiando le lingue parlate dai personaggi protagonisti delle canzoni. Infatti, dice Rosalía nella sua intervista su The Popcast a cura di Jon Caramanica e Joe Coscarelli per il New York Times[2], “le parole sono la scusa per fare l’album.” In principio del suo album erano le parole e una spinta verso la forza creativa della Parola. Un esempio di questo è il brano “Mio Cristo Piange Diamanti”, scritto in italiano in quanto Rosalía prende ispirazione dall’amicizia tra i santi Chiara e Francesco d’Assisi. “Porcelana” mostra, invece, un misto di più lingue. La strofa in giapponese è una scelta intenzionale, in quanto racconta la storia di Ryonen Genso, una bellissima donna che nel 1600 mutilò il proprio volto per poter accedere al monastero buddista, giacché si riteneva che la sua bellezza fosse una distrazione: “Rovinerò la mia bellezza prima che tu la rovini.”

“De madrugá”, ispirata sulla vita di santa Olga di Kiev, include una strofa in ucraino che apre una finestra non solo sulla storia della principessa di Kiev, ma sulla sua vita interiore mentre scatenava la sua vendetta contro i Drevliani: “Non cerco la vendetta. La vendetta cerca me.” Qui la diversità consente all’artista di raggiungere l’obiettivo che si era prefissata, cioè il compimento del pensiero, un compimento che attraversa il vissuto dell’altro. Le diverse lingue non costituiscono ostacoli, ma ponti che collegano una narrazione (un’agiografia) ad un’altra (l’esperienza spirituale della cantante).

È da questo punto che parte l’album- non dalla cantante stessa né da un concetto, bensì dalla “linea focosa”, il “punto giusto” tra ciò che è particolare e ciò che è universale, tra ciò che è dettagliato e ciò che è astratto, tra ciò che è implicito e ciò che è esplicito. Infatti, mentre Lowe cerca di orientare la conversazione sull’album verso una riflessione autobiografica – come dovrebbe fare un bravo giornalista di musica che vuole “demistificare” il processo creativo che sottostà al disco – Rosalía insiste sul fatto che è veramente l’altro che sta al centro dell’ispirazione dietro le canzoni. Un disco profondamente relazionale e dialogico. Una sorgente di curiosità creativa, animata dal desiderio di conoscere meglio l’altro: esercizio che permette all’artista, ma anche all’ascoltatore, di “imparare ad amare meglio l’altro”, spiega Rosalía su The Popcast.

Una richiesta inquieta ed inquietante. Comporre in quattordici lingue diverse, spesso fluttuando da una all’altra, non è un’impresa da poco. Questo sforzo poteva essere facilitato dall’uso dell’intelligenza artificiale: dalla traduzione dei testi alla correzione della sua pronuncia. Un’altra decisione della cantante è stata quella di dare vita a un album umano con un suono umano. L’uso di strumenti acustici e la collaborazione con la London Symphony Orchestra potrebbero essere considerate scelte antiquate per alcuni, mentre per Rosalía è una “decisione conscia”. Anche se sarebbe più facile arrivare dal punto A al punto B con l’IA – spiega l’artista a Zane Lowe – il focus è sull’esperienza tra A e B, in quanto l’attenzione sulla fisicità del suono ci ricorda che “lì dentro c’è un umano”, e che questo album è sull’amore e viene dall’amore.

In confronto allo stile minimalista di Motomami, Lux presenta una certa complessità, liricamente e musicalmente, con cui è arduo sintonizzarsi. Non stretta nella categoria easy listening o mood music ma non è nemmeno radio friendly – si immagini semplicemente di dover fare la spesa mentre l’outro di “Berghain” riecheggia dall’altoparlante del supermercato sotto casa. Rosalía pretende troppo dal suo pubblico? Parlando con Caramanica e Coscarelli, Rosalía critica una certa “pigrizia” che oggi sembra dominare non soltanto l’approccio della società all’arte, ma più in generale, alla vita stessa. “La gente ormai non legge più” – nota Rosalía – chiedendosi se ciò rappresenti un ritorno ad un’era quasi socratica. La risposta dunque è sì: Rosalía pretende troppo. E lei non solo si aspetta questo disagio, ma ce lo augura.

Rosalía ci invita nel buio del bosco per portarci ad uno squarcio di luce. Infatti, il titolo di Lux si ispira all’amato testo di Leonard Cohen, della sua canzone “Anthem” (1992): “There is a crack, a crack in everything. That’s how the light gets in.” La disobbedienza, la testardaggine e la ribellione totale che in Motomami erano così dirompenti, qui vengono trasfigurate. La sua arte diventa un paesaggio poroso in cui luce, lingue diverse, arrangiamenti orchestrali, narrazioni, critiche, devozione, violenza, dubbio, paura, fluiscono dentro e fuori. E in tutto questo fluire e rifluire, l’artista non si perde. Al contrario, non ha mai sentito così vicina la comprensione di se stessa. È una testimonianza di come il dialogo, se sorretto dalla fedeltà alla verità, non faccia perdere l’identità, ma la rivela in un’altra luce. L’incertezza non è qui una mera ricetta per l’incomprensione ma il primo passo verso la domanda che risiede nel cuore di ciascuno, la domanda di cui ognuno è responsabile. “Avere dubbi” – dice Rosalía a Lowe – “è una prova che sei vivo, che quello che fai è veramente vivo.” L’intuizione di Rosalía è giusta quando afferma che “la fede è viva perché in essa c’è del dubbio. Il dubbio ti ricorda che sei qui.”

Rosalía riconosce che il suo lavoro – che qui ricorda molto la teologia – è davvero imperfetto. Spiega che, in quanto umana, qualsiasi opera sarà sempre imperfetta e che la perfezione appartiene solo a Dio, solo al divino. È cosciente del fatto che l’obiettivo della sua arte sia praticamente irraggiungibile in quanto cerca parole e suoni per definire qualcosa che li trascende. È interessante ascoltare come Rosalía definisca la sua vocazione artistica quasi alla stregua di una vocazione religiosa. Racconta al giornalista che durante la sua vita ha sempre pregato Dio per la possibilità di realizzarsi professionalmente come musicista. Da piccola spesso si estraniava dal quotidiano per ascoltare melodie interne alla sua testa, spesso riecheggianti in modo incessante. Lowe risponde ridendo: “Dio è uno stalker”, riferendosi al suo brano “Dios es un stalker”. Attraverso l’udito, attraverso la sua relazione con la musica, Dio le ha rivelato non soltanto la sua chiamata verso Lui, ma anche il Suo movimento verso lei.

Creatività inquieta, fede inquieta. Quale Dio ci rivela Lux? Non è del tutto chiaro per Lowe, ma certo non è in gioco l’immagine di Dio. D’altronde Rosalia si sofferma sull’esperienza religiosa più che sull’oggetto della fede. Nella sua intervista con la rivista Somos[3], Rosalía commenta il mondo d’oggi dominato dalla misinformazione, dall’IA, dalle ideologie, ecc. In un mondo dove è difficile determinare “ciò che è vero e ciò che è torta” – dice in modo scherzoso – “è importante credere in qualcosa, almeno in una cosa.”

Nel buio dell’incertezza, inganno e mancanza di senso, Rosalía non soltanto apre una finestra, ma butta giù la porta, per recuperare una conversazione con il trascendente, il divino, l’angelico, non soltanto per i suoi ascoltatori, ma anche per se stessa. Cresciuta in una famiglia tradizionalmente cattolica, torna alla fede in modo più autentico, provocata dalla curiosità intellettuale e motivata dal desiderio di comprendere l’altro. La fede è strettamente legata alla capacità di amare l’altro (“Da questo tutti sapranno che siete i miei discepoli: se avete amore uni per gli altri.” – Gv 13:35), alla capacità di accogliere l’incertezza, il dubbio e l’inquietudine. Rosalía attualizza le storie dei santi, recupera arrangiamenti orchestrali finora considerati “antiquati”, e ce li ripresenta sotto una nuova luce, una nuova lux. Se qualcosa possiamo imparare dal lavoro di Rosalía, è che questo album è una metafora luminosa di ciò che la fede dovrebbe essere: inquieta, rumorosa, scomoda, ispirata, ribelle, onesta, luce.

Rafaella Figueredo

[1] ROSALÍA. The Lux Interview. The Zane Lowe Interview, in URL: < https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jCcoi3Tzv_Y > (in data 07/11/2025).

[2] Rosalía Explains ‘Lux’: 13 Languages! Heartbreak! Betrayal! Björk! (& ‘Euphoria’), in URL: < https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QEQZs8SLhQE > (in data 07/11/2025).

[3] La metafora dello “spigolare” che qui viene presa in prestito è stata introdotta dal teologo Giuseppe Lorizio in G. Lorizio, Semi del Verbo Segni dei Tempi, Edizioni San Paolo, Milano 2020, 5.

[4] Rosalía revela detalles de “LUX”, su nuevo álbum. Somos in URL: < https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kiD3QqBd_oQ > (in data 07/11/2025).

— riadattato in italiano dall’originale inglese:

Rosalia: A Theologian in This Light

Et lux in tenebrs lucet (John 1:5). This past Friday, November 7th 2025, Rosalia

released her brand new studio album Lux. This album is the fourth in her discography. After

the undeniable success of El Mal Querer (2018), which took home four Latin Grammy

Awards, including Album of the Year, and the Grammy Award for Best Latin Rock or

Alternative Album, Rosalia disrupted the musicscape once more with Motomami (2022), a

“minimalist” – as the Catalan singer describes it – concept album that also thrived in the Latin

Grammys, and that set her apart as an accomplished musician and artist, as she became the

the first woman to win Album of the Year twice.

The accomplishment is far more impressive when one takes into consideration how

vastly different each of these projects differ from each other. The disruption gives us an

insight into who Rosalia is, not only of her musical range and expertise, but also of her

creativity and restlessness. In an interview with Rosalia, the New Zealand music journalist

Zane Lowe catches this behavior and asks her about this “continued mutilation” that happens

when she rejects her earlier creations in order to grow. Rosalia not only recognizes her habit,

but she also hopes that it will continue every day, that every day “identity can die and be born,

and that every day you can decide who you are.”

The choices behind Lux as a creative project are, therefore, extremely intentional,

beginning with the cover it will be judged by. Lux presents a sharp, celestial and – some may

say- rather conservative contrast when compared to Motomami’s cover. The latter features

Rosalia’s naked body covered only by her hands (and by her extremely long manicure). Her

hair is loose and seems to be blown away by the wind, as if she were speeding away on a

motorcycle. What remains unknown is her face which hides behind a rather large motorcycle

helmet with ears. Lux flips all of this to the other side. Rosalia’s hair is neatly tucked away by

her veil and embraces herself in what appears to be a tight, white fabric that reveals the bone

structures of her arms that hug her. The image calls to mind Giuseppe Sanmartino’s Veiled

Christ. In a glowing light, that may come internally or externally, Rosalia unveils her face that

was kept at an arm’s distance in Motomami’s cover.

The first impression of an album matters. Rosalia knows this well. This is why the

release of the first single of an album is so essential to the release and the reception of a

modern pop album. Saying “pop” here does not come without discomfort, but if Rosalia has

taught us anything about her art, it’s that its classification into this or that category seems

superfluous and misleading in understanding that art. Aside from this digression, the first

single Berghain was as intentional as was the cover art. She shares with Lowe that she wanted

to make a simple statement: that Lux is not Motomami. “We are not doing that again”, but the

opposite. It is maximalism against minimalism, a full orchestra that roars at the cuts and loops

that characterized Motomami. Many were quick to assume that Berghain referred to the

notorious Berlin club of the same name, that Rosalia admits she’s “never dared to go to.” She

invites us to a further reflection. The title is referring to its literal meaning in German: a group

of trees in the forest. Rosalia calls us to consider the “labyrinth of woods that exists in every

person’s mind.” Rosalia finds herself standing on the same ground as one Dante Alighieri,

that begins his Divine Comedy finding himself “within a forest dark” (nella selva oscura).

What follows, therefore, cannot be considered anything less than theology: a need for “lux” in

the selva oscura.”

In the light, through the woods, to the other. Rosalia describes her life between albums, a

time of reflection, self-awareness, isolation and study. Rosalia however is not uniquely

introspective or hermetical. She relies on the advice of her most trusted circle, her fellow

producers, friends, family- significantly, of her sister Pili. “Why do you have to destroy the

song always?” Pili questions her artist sister when listening to the tracks off Motomami.

Rosalia recognizes that, initially, she became defensive of her art and tried to justify the

disruption. In fact, some songs on Motomami feel more like a bricolage of different streams

of consciousness rather than the elaboration of one unique thought or narrative. Rosalia

recognizes that as a musician, she is called to make people feel, yet on Motomami she wrote

without finishing the thought, abruptly hitting the brakes before reaching the end. Lux

manifests a desire to go towards completion. She asks herself “How far can I go with this

thought”, while still being free to play and experiment with the arrangements.

To do this, Rosalia stops the high speed chase of Motomami to pay attention to what

her heart is craving. Rosalia reveals that making an album is actually an excuse for her to

study what she wants to study, and here it is the case of theology. If she weren’t in a musical

career – she shares – she would be auditing theology classes at university to learn about

spirituality and to expand her horizons of sainthood. Her curiosity does not limit itself to

Christianity, but she approaches biographies and narratives of “divine” or “mystical” figures

in other religions – the xiān in Taoism, the tzaddikim in Judaism, the rishis in Hinduism, the

awliya Allah (friends of God) in Islam.

Rosalia looks like a theologian in this light. In the year she dedicated to the creation of

the lyrics for Lux, she spent her time reading and writing, creating a mapa mundi and

consulting hagiographies, “all in an attempt to reach the other.” She says to Lowe: “While

collecting stories about the other, […] making songs inspired in that, I’m celebrating and

giving love to the other, to the otherness- trying to understand the otherness better.” She is

aware of the value of her statement. She reflects on how today everything feels so polarized

and divided. She protests: “no! I want the opposite. I need the opposite.”

Rosalia equips herself in her journey to the other through a careful study of the

languages spoken by the characters she channels. In fact, Rosalia says in her Popcast

interview, “the words are an excuse to make an album”. In the beginning of her album were

the words, and a pull towards the creative force of the Word. “Mio Cristo Piange Diamanti”,

written in Italian, Rosalia draws inspiration from the friendship between St. Claire and St.

Francis of Assisi. For this reason, the song is in Italian. “Porcelana” blends multiple

languages. The Japanese verse is intentional, as it tells the story of Ryonen Genso, a beautiful

woman that disfigured her face in order to enter a Buddhist monastery, given that her beauty

was seen as a distraction. “De madrugá”, inspired by the story of St. Olga of Kiev features a

verse in Ukranian that gives us a window not only into the history of the Princess of Kiev, but

also into her interior life (translation of the verse: “I am not looking for vengeance. Vengeance

is looking for me.”) Switching from one language to another could be considered

cacophonous or disruptive. Here, diversity helps reach the completion of thought that Rosalia

set herself as an objective, a completion of thought that passes through the life of the other.

Different tongues are not obstacles rather bridges, verses that connect one narrative (a saint’s

life, for example) to another (Rosalia’s personal experience). It is from this place that Rosalia

begins her album- not from herself nor from a concept but from the “blurry line”, the “sweet

spot” between what is personal and what is universal, what is detailed and what is abstract,

what is implicit and what is explicit. Even as Zane Lowe attempts to steer the conversation

about the album towards an auto-biographical reflection- as a good music journalist should as

he looks to “demystify” the creative process behind it, Rosalia takes back the wheel, insisting

on the fact that the other is truly at the core of the inspiration behind the songs. A profoundly

relational and dialogical album, Rosalia recognizes that there are pieces of herself in her

work, but that it is much more about the other than it is about herself. From a source of

creative curiosity and driven by the want to understand the other better, this exercise permits

the artist, and also the listener, to “learn to love the other better”, as Rosalia shared in her

interview with the New York Times.

Towards higher ground. Composing music in fourteen different languages, often flowing

from one to another is no small feat. This attempt could have been greatly facilitated by the

use of AI, from the translation of the texts to the correction of her pronunciation. Another

intentional decision by the singer was to create a human album with a human sound. The use

of acoustical instruments and a stunning collaboration with the London Symphony Orchestra

may seem like archaic choices for some, yet for Rosalia it is a “conscious decision”. It would

be easier with AI to arrive from point A to point B, but for the artist, the focus is rather on the

experience between A and B. The attention on the physicality of the sound is a reminder that

“there is a human in there”. This album is “about love and from love” – says Rosalia to Zane

Lowe in her Apple Music interview.

Compared to the minimal style of Motomami, Lux presents a certain complexity,

lyrically and musically, that is difficult to keep up with, and that does not exactly fall

underneath the “easy listening”, “mood music”, “radio friendly” category- just imagine

grocery shopping while the outro of “Berghain” booms over the speakers of your local

supermarket. Is Rosalia expecting too much from her listeners? In her exclusive interview

with Popcast, hosted by Jon Caramanica for The New York Times, Rosalia criticizes a certain

laziness that has dominated society’s approach to art, and life, in general. “People don’t read

anymore” – she notes – wondering whether this signifies a return to a quasi Socratic era. The

answer, therefore, is yes; and not only does she expect this discomfort, she encourages it.

Rosalia invites us into the darkness of the woods to bring us to a crack of light. In fact,

the title of her latest album draws inspiration from a beloved lyric by Leonard Cohen in his

1992 song “Anthem”: “There is a crack, a crack in everything. That’s how the light gets in.”

Rosalia’s disobedience, stubbornness, and outright rebellion that in Motomami was so

disruptive, here is transfigured. Her art becomes a porous landscape where light, different

languages, orchestral arrangements, history, critique, devotion, violence, doubt, fear, flow in

and out. And in all this ebbing and flowing, the artist does not lose herself. On the contrary,

Rosalia has never felt closer to understanding herself. It is a testament to how dialogue does

not “contaminate” identity, but clarifies it. Uncertainty is not a recipe for misunderstanding

but it is the first step towards a question, a question that lies in every person’s heart, a

question each one is responsible for. “Having doubt” – Rosalia says to Zane Lowe – “is proof

that you are alive, that what you are doing is truly alive.” Rosalia’s intuition is right as she

goes on to say “faith is alive because there’s doubt in it. The doubt reminds you that you are

here.”

The result cannot be clear-cut. In fact, Rosalia recognizes that her work – which here

looks an awful lot like theology – is imperfect. She explains how any creation that is human

made will always be imperfect, while God and the divine is only perfect. She also recognizes

how the aim of her art is basically impossible as she attempts to find words and sounds for

something that is much beyond them. It is interesting to hear Rosalia unpack her artistic

vocation as she articulates it along the lines of a religious calling. She prayed to be able to be

a musician professionally, and now that she is fulfilling this dream, she notices how in reality,

music was always present. She offers a glimpse of her childhood in her interview with Zane

Lowe. She often disassociated from ordinary life as she tuned into inner melodies that stuck in

her mind, often incessantly. Lowe replies: “God is a stalker”, referencing her track “Dios es

un stalker.” Through her physicality, through her relationship to music, God has revealed not

only her calling to Him, but His movement towards her, an incarnational unveilment that

takes place when she listens without resistance.

Restless creativity, restless faith. Yet what God does Lux as a project unveil? It is unclear for

Lowe, yet he is able to confidently say that what is at hand is definitely not a character

assasination of God. However, he is aware of the fact that the pieces that he gleans from this

God are human, and that often he feels as though God is a relationship. The music journalist

looks an awful lot like a Trinitarian theologian in this light. Rosalia’s intention is not to write

or underline any certain dogma- after all, the musician’s and the theologian’s intents are quite

different. Rather Rosalia focuses on the religious experience of belief rather than the object of

belief itself. In an interview with Somos magazine (El Comercio), Rosalia comments on the

world today- dominated by misinformation, AI, ideologies etc. In a world where it is difficult

to determine “what is real and what is cake” – she jokes lightheartedly – it is important for

people to believe in something, at least in one thing.

In the darkness of uncertainty, deceit, and meaninglessness, Rosalia not only cracks

open a window, she breaks down the door, to recover a conversation with the transcendent,

the divine, the celestial, not only for the listeners, but also for herself. Raised in a traditionally

Catholic household, Rosalia returns to her faith more authentically, stimulated by intellectual

curiosity and motivated by the desire of understanding the other. She has correctly identified

that the credibility of faith lies here: in our ability to love the other (“By this everyone will

know you are my disciples, if you love one another” – John 13:35), but also in the ability to

accept uncertainty, doubt and conversion as an integral part of authentic faith. Rosalia

contextualizes the stories of saints centuries far from us, recovers orchestral arrangements

until recently considered “outdated”, and represents it in a new light, a new lux. If anything is

to be taken from Rosalia’s work, it is that it is a stunning metaphor and example of what faith

should be: restless, loud, uncomfortable, inspired, rebellious, honest.

By Rafaella Figueredo.